My laboratory's no AI policy

Yesterday all my lab's PhD students and our Research Assistant gathered for a pre-Ramadan party, and after we had eaten our fill of delicious pilaf and Bengal curry we had a stern discussion about the use of AI tools in our work at the laboratory. After a couple more relatively innocuous run-ins with AI in various forms in my work (not necessarily connected with anyone in my lab) I have decided I would like to maintain a zero AI policy for all work in English in our lab: that is for writing articles, grant reports, grant submissions, scholarship applications, writing code (in Stata or R!), and for emails. I also want this rule to extend to the use of grammarly, which is not a large language model (LLM) but still provides a lot of language support.

We discussed some of the consequences of AI use and the students' experience of working with AI and their opinion of how other academics use it, and they all agreed to adhere to this new policy. Here I want to briefly explain my reasoning for this ban, and what I think the benefits and disadvantages are, along with a few points about teaching practice and how it relates to AI.

Crime and punishment

First of all, I want to make it clear that I don't, won't and can't punish my students or staff for using AI. First of all this is because I don't use punishment as a part of supervision, because I think it's dumb and counter-productive, but more broadly – as it applies to all aspects of education (such as undergraduate teaching) – I don't think we even can consider punishment for students who use AI. This is because we cannot guarantee that we will detect AI use with high specificity, and if we cannot assure that we will do so, we ethically should not consider punishing people. By specificity I mean, we cannot be sure that our students did not use AI when we read their work. We can ask them, of course, but if they deny it we cannot confirm it. This means that there is a high risk of punishing students for something they didn't do.

This is very different to the problem of plagiarism, where we can be very sure that if the student didn't do it we won't detect it. That doesn't mean we will catch all the times that they did, but when we do catch plagiarism we always have evidence - we can match the text in the student's work to the text in a specific article or website, and make the clear case that they did something wrong. Unfortunately even though LLMs are just huge plagiarism machines, they mix up their theft in such a way that the end-reader cannot detect it.

If you cannot be absolutely certain that someone has done something wrong you shouldn't propose to punish them for it - especially if there is a high risk that you have got it wrong. This is a particular risk with non-native English speakers and AI, because AI uses words and phrases that might seem unusual to native English speakers but are quite common in parts of the non-native English speaking world. Recently African X (Twitter) erupted with rage about this, when a white academic said he rejects all work with a certain word in it, because it's indicative of AI use, but it just so happened that this word is super common in English usage throughout the continent. Oops!

To be clear, I don't punish students for plagiarism during supervision either, I just make clear my disappointment. But my students never plagiarise, because I explain clearly what's wrong with it and why they shouldn't do it and how to avoid accidentally doing it as soon as they start their research with me. So what is needed to establish an AI ban is to explain clearly why I think it's bad, and why it should be avoided.

Two reasons to avoid AI use in graduate education

I have two primary reasons for asking my students to avoid using AI, which I believe are directly related to their future performance and ability in this field, but also tangentially related to the growing problem that AI poses for academia and the transmission of knowledge in our society. The first is the ability of students to check the many mistakes that AI introduces to their work, and the second is about the need for everyone to develop their own writing voice, and to distinguish themselves as writers through it.

Who checks the machines?

In the history of new technologies that improved productivity, it has often been the case that the experts who were the original producers became the managers of the new machines. This happened after the introduction of automated spinning machines, heavy equipment in factories, and even computers, where the first programmers were often the women who had previously performed the calculations that computers were introduced to streamline. These producers were experts in the process that was being improved, and were able to check and monitor the new industrial processes, ensuring that quality did not decline, that the machines did not introduce new problems to the industrial process, and that catastrophic accidents did not happen. Eventually in many cases the machines took over almost all of the production process and the experts – people like my father, for example, who was a typesetter – became redundant, or their field slowly disappeared. There may be a period where that productive technology becomes cheap and easily available to the populace, leading to all manner of dross as the experts lose control of the quality of the process. This happened, for example, with rock music in the 1960s, with website development in the 2000s (think of all those awful myspace websites!) and with video production in the early period of TikTok. But at the industrial level, there is still quality control that distinguishes the rapid production of goods professionally and ensures that machines enhance productivity rather than placing bombs under the factory floor.

But who controls the quality of AI output? LLMs are extremely useful for summarizing and preparing information, and for expanding bullet points into full-length writing. They are great for editing non-native English, for preparing formal emails, and for writing code. But they make many mistakes, including fake references, introducing bugs into code, misunderstanding publicly available information, and getting basic facts wrong. They also have a specific tone and style of writing that is not necessarily suited to the context. In the academic context the experts in the industrial process who should be guiding these machines in the industrialization of our cottage industry are not the students, who are apprentices in the analogy of the industrial revolution, but the professors, who are the experts guiding the production of knowledge.

But students don't typically check the content of this work, because:

- They don't have time to produce the output they need, and are not skilled enough to produce it in the available time, so they fake it with the help of the machine

- They don't have the ability to produce the material or to write the content, and the machine superficially does

- Their supervisor is demanding or unforgiving, and the emotional and personal trouble of dealing with his or her behavior is too great, but the machine can produce material that superficially soothes this behavior (since on the surface it looks good), and this enables them to pass work through their boss

- The discipline or lab has no standards of quality, so it's easy to be very productive using a machine that produces "results" quickly

These are all reasons that mitigate against quality control, and often occur when the supervisor(s) and/or disciplinary leaders don't put sufficient attention on the work being done. An AI producing mistakes, coupled with a boss who demands high output and behaves badly towards imperfect work, is a perfect environment to produce errors that multiply through every level of knowledge production, culminating in badly written papers full of errors.

I don't think that I'm the type of demanding and unpleasant supervisor who pushes students to produce lots of low-quality work and gets mad at mistakes, but even in a good work environment, students who use AI aren't qualified to check it, and that will generate errors that propagate through work and ultimately undermine the quality of their and their lab's work.

Incidentally, I think one day these errors, if not carefully guarded against, are going to end up in the software for an aircraft or a train network. We really need to make sure AI is not involved in any of the things that make our society work!

How human voices will win

The second problem with using AI to write is its awful, cloying, saccharine voice. AI's default writing style is a pleasant, easy-reading formal language that is perfect for writing reports and essays and is superficially "professional". But this voice is anodyne, boring, and full of simpering platitudes and empty rhetoric that hides more than it reveals. It is also repetitive, using a small number of business-speak words and phrases that tell us nothing, George Orwell's famous "fly-blown cliches" of political writing, deployed as consultant-speak. With AI you read phrases like this:

- The model employed multi-level mixed effect models, leveraging available information to give more detailed insights into factors affecting X

- This approach enabled data analysis in diverse contexts

- This research provides information that will be invaluable for informing policy-makers in the field of Y

These sentences can all be deleted from your work without changing anything you said. They sound like they are telling you something, but they're not. They are the "more research is needed" in your conclusion, the "appropriate decisions were made" of your methods section, the "X is a major issue" of your introduction. They are words without purpose, and much of AI writing is like this.

I don't personally believe that AI is going to last, I think it's a boom like crypto and when the bottom falls out of its apparent market all the grifters and scammers who're talking about how AGI is just around the corner will move on to their next scam for milking venture capital, and we'll all be free of them. But if AI does last, we can look forward to an academic world where its insipid, asinine phrases become ubiquitous. Grant-making bodies, journal editors, book publishers, candidate selection panels and university entrance assessors will find themselves flooded with millions of pages of this dross, all written in the exact same boilerplate style, trying to find the real content of these applications, articles, books and statements of purpose from amongst this swamp of deadened prose.

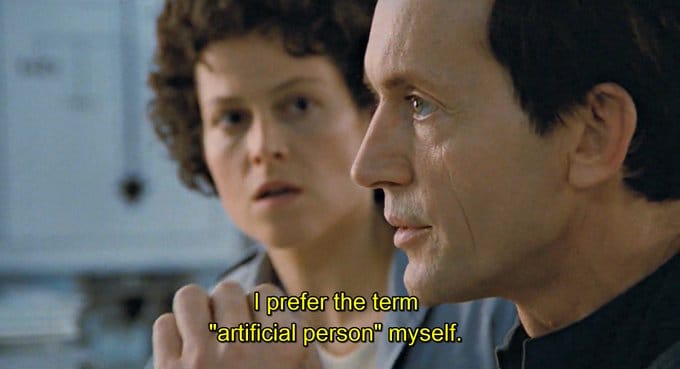

If you have your own voice in that world you will be like the character from that movie about the guy who discovers lying. You will stand out, your voice will be valued, and everyone will listen to you. This is particularly important for academics, who need to be able to change the voice with which they write according to their purpose and audience. The style I used for this post was not the same as the style I use to write a technical article, which is different again to the moralizing and firm tone I use in a correspondence about Gaza, or the more inspired and optimistic language of a grant application, or the supplicatory but confident tone of a job application. If you want to be successful in communicating ideas you need to be able to change the register and style of how you write ideas. But doing that requires you to develop your own skill in writing, and to carefully edit and mould your work into the form it needs to be.

LLMs can change their style, but it's not easy to get them to do so. I can tell Deepseek to paraphrase Lenin in the style of Quellcrist Falconer, but Richard Morgan had to write her voice originally. I can ask chatGPT to write like Shakespeare, but only because Shakespeare already made the effort. I can ask chatGPT to write in a slightly more or less formal style, to change the type of language used, and to modify the length or rhythm, but the only way I'll be able to do that well is if I am already able to write that way myself.

If my students are going to excel in academia they need to develop their own voice, and be able to modulate and shift that voice depending on who they are talking to, why they're talking, and what they want to say. And as the world fills with AI slop that ability will become more valuable, more noticeable, and more worthwhile.

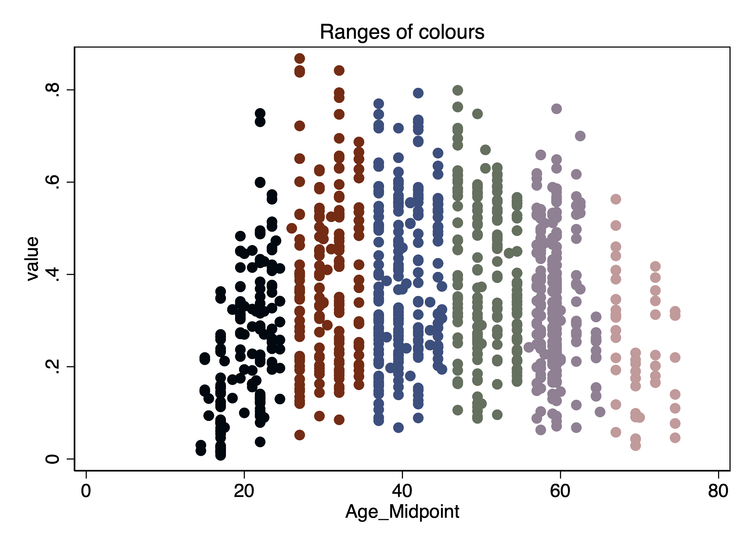

How my students experience AI

After my little lecture the students discussed how they use and experience AI. One student told me that he has found his ability to write R code has declined as he has relied more on AI to help him (it does this now in some IDEs). Another told me he thinks that about 90% of academics and students use it, and there are many youTube videos now about the urgency of using it to improve productivity. Another student revealed that she uses it for contacting strangers and that it is useful for grammar advice. They all think it is widespread and that a lot of professors now use it for their work.

I think my students would be profoundly disappointed if they discovered I used AI to prepare class material, to write emails or to write assessments of their work. Imagine if you failed to get a job and then discovered your supervisor had asked chatGPT to write your recommendation letter! But at the same time they can see others around them beginning to use it a lot, and fear they will be left behind in productivity if they are not using it. We also talked about how students learn to write. All my students bar one are non-native speakers of English, all of them come from nations outside the imperial core that are not viewed favourably in academia, and all of them worry how the presentation of their work will be received in that context. In this conversation I told them about my experience of native English speaking students, who are also usually terrible writers, and about my own experience when I was young of being constantly corrected by my boss (Ingrid van Beek), who drilled into me the importance of voice and attention to crafting our language.

These are challenges that we as supervisors need to confront and deal with.

The role of supervisors in managing AI

I am aware that many students have lazy, disengaged or just plain unpleasant supervisors. If your supervisor doesn't check your work, isn't actually very interested in quality, or treats you badly when you make mistakes, you are going to need AI to help you with your writing. But good supervisors should not do this. A good supervisor should provide detailed, regular feedback on your work, with explanations about why they made corrections and how they expect language to be used. They should check their student's work closely, pay attention to the details of the content, and give careful feedback. They should explain why they make certain decisions, what will happen when corners get cut and why shortcuts are sometimes necessary. They should help students to see their work in the context of academic integrity, scientific correctness, and the institutional pressures that shape the way that we work in academia.

If supervisors do those things then students don't need to use AI, because they will get much more benefit from presenting the work they're capable of doing, and receiving corrections. So if you, as a supervisor, don't want to read AI – if you think you can't be bothered reading something your student couldn't be bothered writing – then you need to be constantly editing, providing feedback, checking your students' work and explaining what you're thinking and why you're doing things. You also need to give your students opportunities to test themselves and their writing in different contexts and styles. It's hard work!

My lab has a rule that nothing important gets sent, submitted, uploaded or presented in English without me checking it. Sometimes, obviously, things are last minute and we don't have time to get proper feedback or to turn some tedious, last-minute scholarship application into a learning experience. But as much as possible, we should. And when supervisors help their students in this way, students develop real skill and flexibility in writing, find their own voice, and will be able to confidently write for every circumstance. They will not develop those skills if every time they do any original work they hand the final, tedious writing task to a glorified toaster.

Conclusion

My policy in my lab is for my students to avoid using AI for any tasks, so that they can learn from their mistakes, get used to writing, and develop their own voice. Doing that requires effort and attention from them and me, and I appreciate that such a policy is not possible or even advisable for some students in some educational environments. But if you are a good supervisor who values the future of your students, and if you're worried about what is happening to our academic environment as it fills with AI slop, then I suggest you implement this rule in your lab as well. No AI for any tasks, ever – value your skill and have faith in your students, so that they can develop the skill to present their own ideas in a world slowly being stifled by intellectual slop.